Curious memoirs of the pastimes of the building's former inmates, these bone gaming pieces and other items such as domino and die, appear to have been hand-fashioned and decorated. Records show that the rations provided for the convict and women inmates of the building generally allowed for daily servings of meat. This is confirmed by the recovery during archaeological investigations of thousands of pieces of sheep, cattle and pig bones. The gaming pieces therefore offer us some evidence of resourcefulness, with convicts or perhaps the women who later inhabited the building, manufacturing these items for themselves from the remains of bland mess hall dinners. These gaming pieces can also be looked upon as remnants of the inmates' resistance to authority. The superintendent of convicts, for example was expected to "use his utmost endeavours to effectually prohibit and prevent" gambling among men - yet his "utmost endeavours" are confirmed to have been not enough to curb illicit activity, as evidenced in the recovery of many artefacts with which the men might have been subverting the rules.

Hyde Park Barracks Museum

This Georgian building was designed by the convict architect Francis Greenway as sleeping quarters of 600 male convicts (1819-1848). Subsequently it housed immigrant girls and asylum women (1848-1886) and legal offices and courts eventually occupied the entire site (1887-1979). It has been refurbished as a museum about itself, and its displays include relics, pictures, plans and models exploring the sites past and present. A special feature is reconstructed convict dormitories, which are periodically available to sleep in overnight, with a convict breakfast served at dawn. The building also houses the Greenway Gallery (see separate entry). Interpretive displays within the building and grounds highlight many aspects of the barracks history.

Items

Recreational

Gaming Pieces

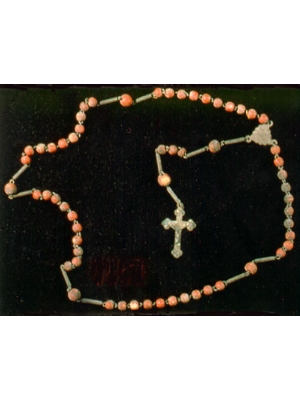

Rosary

Rosary Beads

The Hyde Park Barracks archaeology collection contains a vast amount of material salvaged by the building rats. The rodents stole from the immigrant women's books, textiles, jewellery, paper and other objects and dragged them beneath the floor. The photographed item would have laid remarkably undisturbed until quite recently when archaelogical investigations took place in the 1980's. Presumably the rosary beads belonged to one of the many Catholic immigrant girls who came to the colony to either reunite with family, to find employment or to escape the Poor Laws. For whatever reason, all of the immigrant women were escorted at every stage of their journey by moral guardians such as clergy and chaperones who undoubtedly tried to orchestrate their encounters in this land. The outward devotion of the immigrant women may be exemplefied by the inscription on the rosary beads "Oh Mary, without sin".

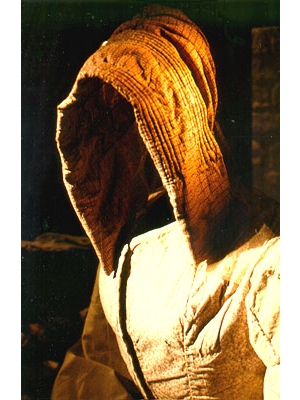

Womens Head-Wear

Bonnet

The photographed item is one of several bonnets in the Hyde Park Barracks collection, and one of the thousands of objects recovered from the rat's nests during archaeological investigations in 1980/81. The rats unknowingly created a unique and significant collection of clothing belonging to nineteenth century working class women, including stockings, scarves, shoes, a bodice and aprons. The bonnets provide a poignant glimpse of the daily lives and dimensions of the many women who passed through Hyde Park Barracks while waiting to go "into service". The handiwork evident in the bonnet - along with other archaelogical finds such as needles, buttons, thimbles and fabric - provides an image of the pastimes and regulation of these women, who were "permitted to employ themselves at sewing, reading & cooking" during their days of waiting.

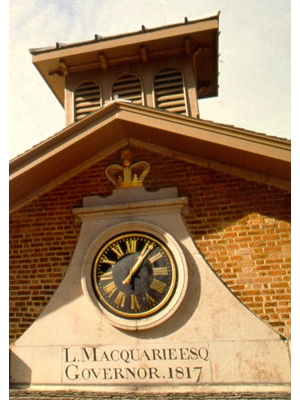

Timepiece

Clock

This clock on the Western gable of Hyde Park Barracks has worked continuously since 1819, when it first fulfilled the role of regulating the lives of the building's inhabitants. It has watched over 180 years of the Barracks' use, overseen many thousands of occupants and visitors, and survived many changes to the building's appearance and fabric. More recently, it has been the subject of some debate, as historians, museum curators, clock enthusiasts and archaeologists have sought to silence doubts about its true origins. The clock was long believed to be the work of convict clockmaker James Oatley, who was paid the hefty sum of 75 pounds for work on it in 1818. Oatley also received 30 pounds per year for work as "Keeper of the Town Clock". Twentieth century horologists, however, questioned that such a large and sophisticated mechanism was able to be constructed in the colony at such an early date, and various experts have since concluded that the mechanism was produced in the workshop of Benjamin Lewis Vuillamy, clockmaker to King George III, owing to features such as its escapement and housing. "Vuillamy, London", is clearly visible on the pendulum. What , then, explains the 75 pounds paid to James Oatley? Experts have concluded that the present clock perhaps replaces one manufatured and installed by James Oatley in 1818. Oatley's original clock hands and dial - the latter possibly fashioned from recycled copper sheathing plates fitted to the hulls of wooden ships - have been retained, fastened to the later (currently existing) Vuillamy movement. Oatley, some years later, was granted 30 acres of land in Sydney's South - the area is now a Sydney suburb and still bears his name.

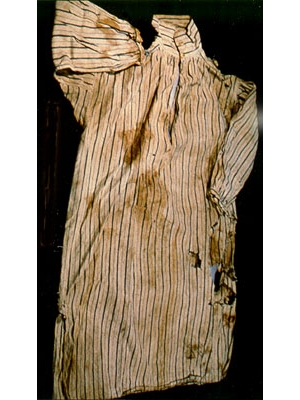

Shirt

Convict Shirt

Convict uniforms varied throughout the colonies and between different institutions depending upon the availability of clothing supplies. Although uniforms tended to be coarse, loose-fitting and ready made, the colours and styles varied - blue was a colour popular early on, while yellow, grey and even red were in use by 1817. By the 1820's labels were added to clothing as a way of signifying government property - these included conspicuous broad arrows, and initials such as PB or CB for the Prisoners Barracks or Carters Barracks. The stamp "B.O", for Board of Ordinance (the government department supplying clothing to various penal settlements in the 1820's) has also been found on examples of convict clothing. Between 1819 and 1848, the Barracks housed male convicts who were in government employment. The men were issued a uniform which consisted of a short jacket, trousers, cotton shirts, a woollen hat and handkerchief. It is possible to conclude that this shirt, given the broad arrow and "B.O" marking, was issued to and worn by a male convict serving his time here. The shirt was, like much of the Hyde Park Barracks archaeological collection, was recovered from underneath the floorboards.